German Compensation Debt to Poland

German Compensation Debt to Poland

‘President Karol Nawrocki has announced that he will raise the subject of reparations during his talks in Berlin. Rightly so. Yet the word “reparations” is only a symbol and a rhetorical device that conceals a whole series of issues. In short, they can be summed up as the German compensation debt to Poland. President Nawrocki will demand redress for Poland’s suffering. And, I hope, he will dismantle the illusion of a deceptive Polish–German reconciliation established on German terms and, sadly, with the involvement of a fraction of the Polish elite,’ writes Prof. Stanisław ŻERKO

.The position of every government of the Federal Republic of Germany – from Adenauer to Merz – has been consistent not only on the question of reparations for Poland but also on compensation for Polish victims of German crimes committed between 1939 and 1945. From Berlin’s perspective, neither Poland nor Polish victims are due compensation, because on 23 August 1953 the communist government of the Polish People’s Republic, headed by Prime Minister Bolesław Bierut – who was concurrently First Secretary of the PZPR and a loyal Kremlin agent – issued a statement renouncing further German reparations. This followed an identical move by the Soviets and came just two months after Russian tanks crushed the workers’ uprising in East Berlin and many other East German cities. Moscow decided to ease restrictions on its former occupation zone, having previously removed nearly all portable assets under the guise of reparations.

There can be no doubt that Bierut and his ministers had no say in the matter. In 1953, Poland’s post-war dependence on the Soviet Union was at a peak. Incidentally, had it not been for the German aggression against Poland on 1 September 1939, there would have been no Bierut government in Warsaw in the first place – and above all, there would have been no staggering human and material losses inflicted on Poland. One direct consequence of that aggression was Poland’s relegation to the role of a Soviet satellite, forced to endure both a communist regime and a Stalinist-style command economy. For the German government to rely on a declaration coerced from a puppet administration led by Bierut, Stalin’s proxy in Warsaw, is – I have no hesitation in saying – a despicable act.

To be clear, Poland did receive reparations from Germany between 1945 and 1953. They were granted at the Potsdam Conference, separate from the transfer of German territories east of the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers. These so-called Western and Northern Territories (also known as the ‘Recovered Lands’) were handed to Poland by the Big Three not as reparations but as compensation for half of the Second Republic annexed by the USSR. Reparations were to come on top of this. Unfortunately, as a smaller state, Poland was not to receive them directly, but rather through the Soviet Union. Two weeks after Potsdam, Moscow forced the communist government in Warsaw to sign an ‘implementation agreement’ under which Poland was to obtain 15 per cent of the reparations collected by the Soviets, even though the base for that calculation was never specified. What is more, during the reparations period, the Warsaw government was obliged to deliver millions of tonnes of coal annually to the USSR (between eight and thirteen million) at a ‘special contractual price’ far below global market level. The revenue barely covered the cost of mining and transporting the coal to the western border. In practice, the value of what Poland actually received was negligible. The losses to the Polish economy were all the greater because this coincided with a boom in global demand for coal, which could have generated valuable hard currency for the battered country. Worse still, the Soviets sometimes compelled Poland to accept deliveries of dubious worth. In 1949, for example, the list of reparations goods included six million Polish-language copies of works by Marx, Lenin and Stalin, printed in East Germany and valued at ten per cent of that year’s reparations shipments.

In the following years, even Polish communists tried to secure at least compensation for the victims of the German occupation. Yet Bonn insisted that Bierut had renounced not only reparations but also victim compensation. Berlin maintains this stance to this day. West German authorities also contrived other tricks to block Polish victims from even filing claims. They pointed, for instance, to the absence of diplomatic relations between the Polish People’s Republic and the Federal Republic. But when relations were finally established in 1972, the deadline for filing claims had already come and gone on 31 December 1969. It should be emphasised that the lack of diplomatic ties between the FRG and Israel prior to 1965 did not hinder the 1952 Luxembourg Agreement, under which West Germany provided 3.5 billion DM in reparations to Israel and Jewish organisations worldwide – more than ten per cent of the federal budget in the year the deal was signed. Polish victims, trapped behind the Iron Curtain, were treated by West Germans as victims of a lesser category.

During his visit to Bonn, Stefan Olszowski, Foreign Minister of the Polish People’s Republic, was told by Chancellor Willy Brandt, a Social Democrat, that there had been internal resistance regarding compensation, particularly from ‘the younger generation, who did not feel responsible for the transgressions of the older generation nor wished to be associated with their misdeeds and crimes.’ Meanwhile, liberal foreign minister of West Germany, Walter Scheel – who later became president – reached for a whole arsenal of convoluted legal pretexts to undermine Poland’s claims. He even maintained that such matters could only be addressed once Germany was reunified. Olszowski summed up Poland’s position in a pointed remark: ‘We must not fetishise formalities, for they matter less than the hopes and expectations of the people. Laws are made by people, and it is the duty of people to make laws that serve them.’

Six months later, in Poznań, Edward Gierek declared that ‘the account of wrongs inflicted on the Polish nation by criminal Hitlerism has not yet been settled, nor the losses that our society will continue to feel for a long time. These are matters of great importance, both politically and morally.’ Throughout the latter half of the 1980s, the Polish foreign ministry continued to submit diplomatic notes to Bonn, seeking reparations (specifically in 1986 and 1988). The notes explicitly denied that Poland had renounced all claims in 1953. West Germany countered by arguing that the 1953 London Debt Agreement had suspended the matter of reparations until a peace treaty was signed. In November 1989, President Wojciech Jaruzelski wrote to his West German counterpart, Richard von Weizsäcker, about the need for ‘moral and material compensation’ for those who survived the terror and occupation of wartime Germany.

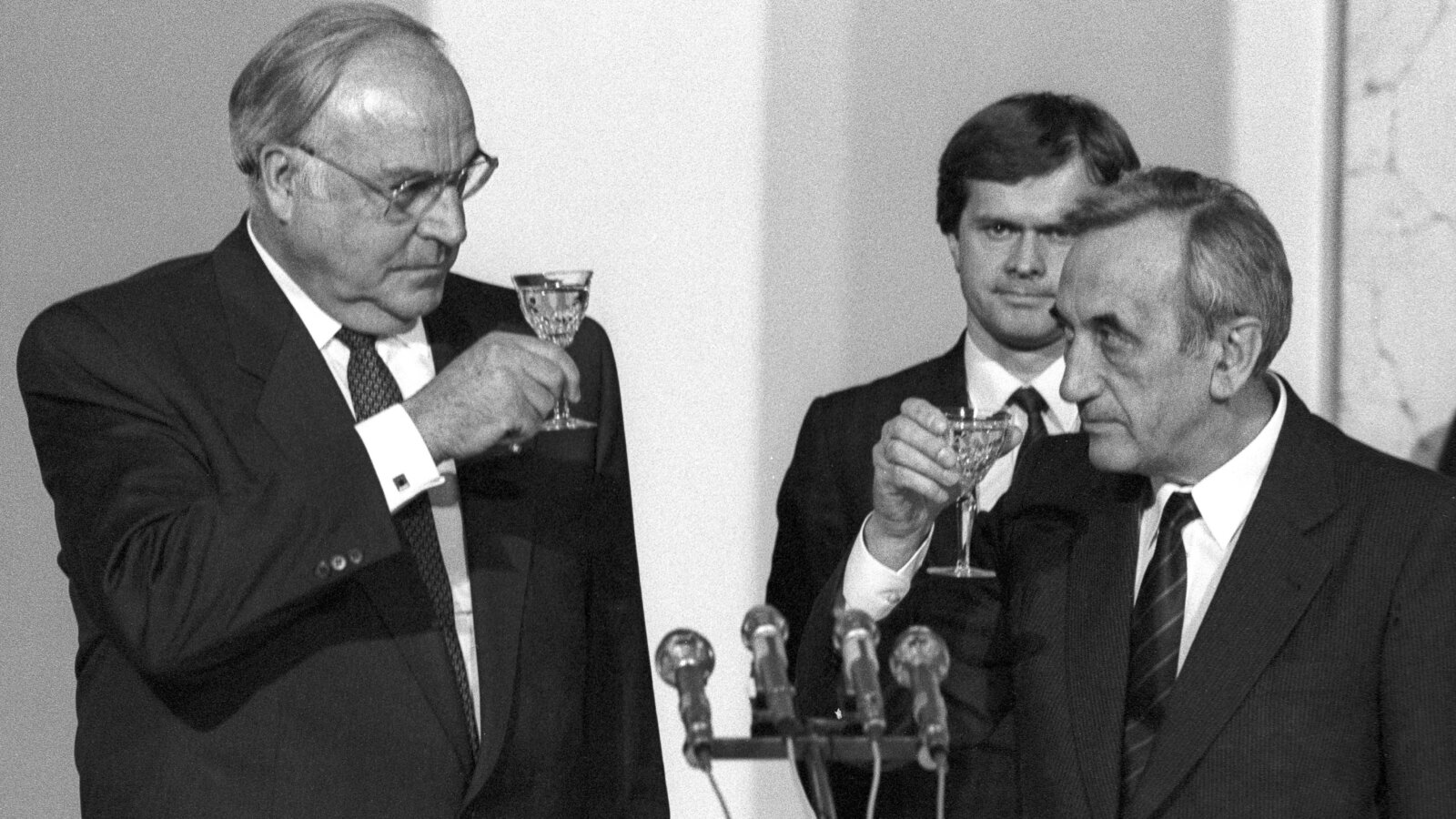

For forty years, the necessity of a peace treaty was the cornerstone of West German doctrine in international law. On November 8, 1989, Chancellor Helmut Kohl was still telling the Bundestag about the need to sign such a treaty. But just a few days later, when the prospect of a swift reunification emerged, Kohl changed his position and did everything in his power to prevent a conference at which the treaty might have been drafted. He was afraid that the issues of reparations and compensation would arise. Supported by the United States, he achieved his goal – the matter of a peace conference and a treaty simply vanished, as though the Bonn government had not sought it for four decades. It was, as Professor Michael Stürmer proudly wrote in Die Welt in September 2017, a ‘masterstroke of German foreign policy.’ Stürmer, well known in Poland for his apologetic biography of Putin, could not have sounded more pleased with his chancellor.

Kohl succeeded thanks to brazen falsehoods and by exploiting Poland’s weakness as it slid deeper into economic crisis. During his talks with President George H. W. Bush at Camp David on 24–25 February 1990, the chancellor persuaded the American leader that raising the reparations issue would delay German reunification and must therefore be avoided. He assured Bush that the FRG had already paid more than 100 billion DM in compensation, of which Poland had supposedly received ‘grosse Summen.’ In reality, these ‘large sums’ amounted to just 100 million DM, paid under the 1972 agreement to Polish victims of pseudo-medical experiments in concentration camps. It was not even one per cent, but a mere one per mille of the total figure Kohl cited.

The chancellor made no secret of how deeply he was rattled by the words of Sejm Marshal Professor Mikołaj Kozakiewicz, who had visited Bonn in December 1989. Kozakiewicz declared that Poles expected 200 billion DM and stressed that settling the issue was a precondition for any future Polish–German reconciliation.

Kohl, worried by this and insecure about the standing of the 1953 Bierut government’s declaration, became intent on securing confirmation from Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s government. At one point, he even considered making recognition of Poland’s western border by a reunified Germany conditional on Poland’s reaffirmation of the 1953 declaration. His coalition partner, Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, dissuaded him in early March 1990, fearing an international scandal. Kohl then backtracked, claiming he had been misunderstood and that he had never intended to make such a linkage. In a telephone conversation with French President François Mitterrand on 14 March 1990, he was already insisting that he placed no conditions on Poland but ‘merely expressed a wish’ that Warsaw ‘once again confirm what it had already stated on the matter of compensation (…) in 1953 and 1989’ [a slip of the tongue – he presumably meant 1970; author’s note].

As reported by Daniel Luliński in Trybuna Ludu, Kohl made the following statement in an ‘off the record’ conversation with a small group of selected journalists two days earlier: ‘I know the Poles. I must be cautious, and I cannot let the issue of reparations just sit on the table. It was put there twenty years ago under earlier chancellors, and it has stayed there ever since.’ The remark laid bare Kohl’s unease – he dreaded above all that the Bierut government’s declaration might be called into question.

Published German documents leave no doubt that it was precisely the spectre of Polish reparations claims that led the FRG government to reject the idea of a peace treaty, despite having pressed for one for forty years. Kohl’s adviser Horst Teltschik (whose 1989–1990 diary is also available in Polish) noted that this approach would allow the federal government to argue that reunification itself closed the reparations issue once and for all. The strategy worked: on 30 April 1990 it was agreed that what would be negotiated was a Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, not a peace treaty. This so-called Two Plus Four Agreement concluded between the two German states and the four former occupying powers was signed in Moscow on 12 September 1990. On 3 October, German reunification formally came into effect.

The Mazowiecki government faced an extraordinarily difficult economic situation. Poland, mired in crisis, was heavily indebted to the West – above all to the FRG – and desperately in need of foreign investment, including German capital. The question of reparations and compensation was therefore dropped. The damage was compounded by the agreement signed with Germany by Jan Krzysztof Bielecki’s government, the so-called Żabiński–Kastrup accord of 16 October 1991. Under its terms, the Polish government pledged not to support compensation claims by Polish victims of the German occupation. In return, the FRG provided 500 million DM to the Foundation for Polish–German Reconciliation, which was tasked with distributing the money among the surviving ‘victims of Nazi persecution,’ chiefly former concentration camp inmates. The sum was pitifully small, and in any case the payments were delivered as ex gratia humanitarian aid. Earlier, on 8 November 1990, Kohl had told Mazowiecki that this must not be presented as compensation but as ‘support or assistance,’ since ‘a former Polish government had already renounced compensation.’ Kohl had every reason to feel satisfied: Poles had been waved away with a token amount. Financial assistance from the Foundation was available only to those alive on 8 January 1992, i.e. the date when the first tranche of German money reached its account. To this day the Foundation’s website stresses that the funds disbursed ‘were not compensation but symbolic humanitarian aid from Germany for victims of Nazi persecution in Poland.’

Only after years of difficult international negotiations involving the U.S. government and Jewish organisations did Germany agree to a one-time ex gratia payment to former Polish forced labourers, with an agreement signed in 2000. The payouts ended in 2006, covering 484,000 people for a total sum exceeding 3.5 billion zloty.

It is estimated that all three of the affected groups received compensation under the agreements of 1972, 1991 and 2000 (according to professors Jerzy Sułek and Jan Barcz). Meanwhile, a detailed report on Poland’s wartime losses calculated the figure to be more than 6 trillion zloty. Against this backdrop, the material redress that the Federal Republic provided Poland for the Second World War looks negligible indeed.

Millions of Polish victims died without ever receiving a shred of ‘humanitarian aid’ from Germany. There were also groups of survivors excluded from all three compensation schemes. Among them was Winicjusz Natoniewski, who at the age of five survived the pacification of his village, Szczecyn in Lublin Province. He narrowly escaped a massacre that claimed the lives of 360 of his neighbours, leaving him with disfiguring scars. He tried to pursue justice individually against Germany in a Polish court but was blocked by the doctrine of state jurisdictional immunity.

Poland rebuilt itself after the war unleashed by Germany through its own efforts – unlike the Federal Republic, it was denied U.S. assistance under the Marshall Plan at Stalin’s command. Poland can, of course, get by without German payments. But Poles will remember how they were treated by the Federal Republic. And they will be fully aware of how hollow the moving, eloquent speeches delivered on anniversaries such as the 1 August or 1 September actually are. They will see how Germany’s claim that reparations were legally closed by Stalin’s representative in Warsaw clashes with its assurances of a desire for reconciliation with the Polish nation.

.It’s often said, somewhat ironically, that Germany is a Moralmacht, which means a ‘moral power.’ Germans have a marked tendency to lecture others, to present themselves as a nation that has dealt exemplarily with its criminal past. They insist, with tireless repetition, that foreign policy must be grounded in values, morality and ethics. And yet German chancellors, their spokesmen and German ambassadors in Warsaw invoke a document extorted from the Polish nation by Bierut’s puppet government in 1953 to dismiss as baseless any expectation of even partial material redress for Poland. This is hypocrisy in its purest form. Such a deceitful basis will never allow for real reconciliation between Poland and Germany. Let us recall the wise words of the resolution adopted by the Polish Sejm on 14 September 2022: ‘The wrongs suffered by millions of Poles will cry out until they are fairly redressed.’